As China continues to reopen its economy and reinvigorate its diplomatic dealings around the world after three years of strict COVID-19 restrictions, Beijing has its sights set on Central Asia, analysts and officials say.

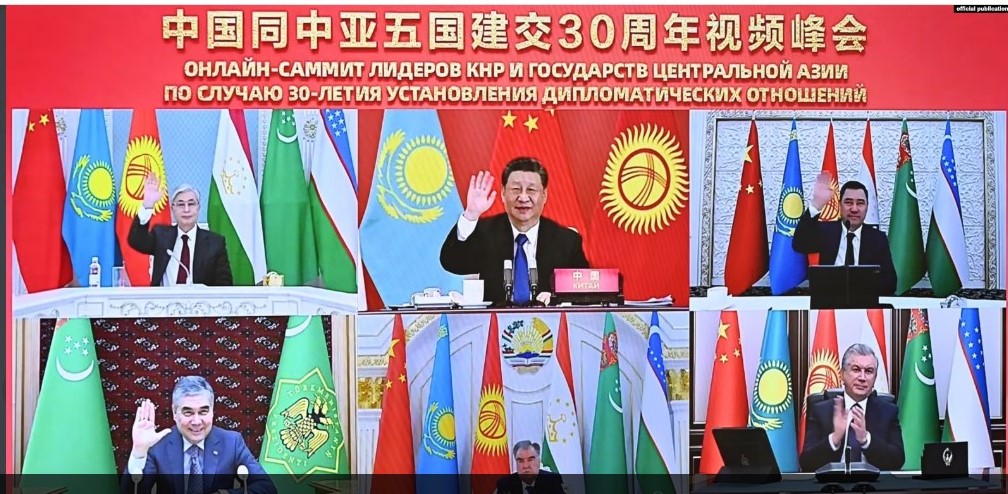

As trade and commerce links between Beijing and the five countries in Central Asia continue to rebound from the shutdowns caused by the pandemic, Chinese leader Xi Jinping will hold Beijing’s first in-person summit with Central Asian leaders on May 18-19 in Xi’an.

China will use the summit to try to build on the major progress it has made recently by establishing visa-free travel deals with several regional governments.

A new draft law between Kazakhstan and China that allows passport holders of the countries to stay in the other country for 30 days has been approved by Astana and is expected be signed into force later this month at the summit in Xi’an.* The move comes after Uzbekistan approved two weeks of visa-free travel for Chinese tourists and with Kyrgyzstan currently in talks for its own visa-free regime with Beijing that it hopes will boost its economy through increased cross-border trade, investment, and tourism.

“We’ve discussed visa issues for our citizens, including for truck drivers [and] also about the introduction of a visa-free regime,” Kyrgyz Foreign Minister Jeenbek Kulubaev told the country’s parliament on May 3 while discussing a recent meeting with his Chinese counterpart, Qin Gang. “Now our side has to do the work…but in general, China is ready to discuss and is open to dialogue.”

The current push in Central Asia comes as China looks to breathe new life into its multibillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) foreign-policy project and attempt to normalize the situation in its western Xinjiang Province, which borders Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. China views Central Asia as integral to its long-term economic strategy for Eurasia and experts say Beijing is looking to send a symbolic message to the region as its domestic economy gathers steam again since its reopening.

“China’s image and its trade relationship took a hit during the pandemic when Beijing closed its borders [with Central Asia],” Raffaello Pantucci, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, told RFE/RL. “The assumption here is that this can bring economic benefits, but it’s also a clear message that China is open for business and that Central Asia is open to China.”

A New Chapter

Beyond the rigid COVID-restrictions in China during the pandemic that led to a major drop in cross-border trade, Xinjiang saw stricter border controls come into effect ahead of a multiyear repression campaign launched by Beijing against Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in the western province such as ethnic Kazakhs and Kyrgyz.

That expansive campaign in Xinjiang — which included detention camps and prisons as well as forced labor and birth control, among other abuses — led to what a 2022 UN report called “serious human-rights violations” and recognized as genocide by several Western parliaments.

In Central Asia, the crackdown became a flashpoint for activism due to family connections, particularly between Kazakhs and Xinjiang’s ethnic Kazakhs, with several former detainees publishing testimonies after fleeing China for the Central Asian country.

The Kazakh government and its Central Asian peers have since silenced most forms of activism about Xinjiang, with only a select few relatives of those missing in Xinjiang still willing to protest in the face of continued repression.

Central Asian governments now have their sights set on reaping the economic rewards of a reopened China and increasing trade links with neighboring Xinjiang.

“This will dramatically increase the flexibility of Kazakh business and its ability to provide not only local, but also the Central Asian, Eurasian, and Chinese markets with the necessary goods. This will also provide more investment opportunities,” Adil Kaukenov, an expert at the state-run Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies in Astana wrote on April 13 when legislation for the visa-free deal was approved.

Xinjiang’s importance is underlined by the fact that the province alone accounts for 40 percent of total Chinese-Kazakh trade, according to Kazakh government statistics.

As a whole, China’s economic footprint in Central Asia is growing despite the pandemic-caused setbacks. By the end of 2020, total Chinese investment in the region reached $40 billion, a figure that grew to $70 billion by the end of 2022.

Kazakhstan continues to account for a leading percentage of Chinese capital in the region. In addition to being a leading site of investment, Chinese-Kazakh trade grew by 33 percent year-on-year in 2022 to set a new record of $24 billion — and local officials are seeking to increase it further.

During a March visit, Kazakh President Qasym-Zhomart Toqaev welcomed Xinjiang Communist Party Secretary Ma Xingrui and a visiting trade delegation to Astana, where the countries signed $565 million worth of new contracts.

Astana also continues to position itself to capitalize as a key transit point for ferrying goods overland between China and Europe, as Kazakhstan aims to fill the void left as shipping companies look to bypass Russia — which had been the main transit route — due to sanction risks caused by its full-scale invasion of Ukraine more than a year ago.

Kazakhstan and other countries like Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey are trying to boost investment and interest in the Middle Corridor — also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route — a transit route under the guise of the BRI that links East Asia and Europe via Central Asia and the Caucasus.

“In principle, China’s relationship with Central Asia hasn’t changed a lot,” said Pantucci, who is the author of Sinostan: China’s Inadvertent Empire. “It’s seen as integral to Xinjiang’s security and development and it’s clearly a region where Xi and the Chinese government are comfortable and continue to cultivate better ties.”

A Milestone Summit

The focus on boosting regional infrastructure and connectivity will follow Beijing as it holds the high-profile summit with Central Asian leaders in Xi’an, which will be chaired by Xi. It marks the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union that a Chinese leader will host all five Central Asian heads of state.

Chinese officials have already said the summit will showcase burgeoning trade between Beijing and the region, with Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin telling reporters on May 8 that it will be a milestone that heralds “a new era of cooperation.” He added that an “important political document” is due to be signed that will “draw a new blueprint for China-Central Asia relations.”

Wang did not go into detail about the agenda, but the summit will be closely watched as Central Asia navigates the political and economic fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Haiyun Ma, a professor at Frostburg State University who studies Beijing’s relations with Russia and Central and South Asian countries, told RFE/RL.

Ma said the direct economic benefits from measures like the new visa-free deals are still unclear, but they are an important symbol for Beijing’s growing sway and the regional reordering under way as China grows its ties with Moscow but continues to pursue its interests in Central Asia, where Russia has traditionally guarded its influence.

The war in Ukraine has proved awkward for Central Asians as they looked to forge new long-term economic relationships with other countries, leverage concessions from Moscow because of its weakened status, and distance themselves from the Kremlin politically.

Despite Moscow’s diminished stature, however, it continues to be a key player in the region.

It’s continued influence was on full display as all five Central Asian leaders hurriedly came to Moscow for the May 9 Victory Day, which many analysts viewed as a result of Kremlin pressure.

With that in mind, Ma added that Beijing will use the summit to reassure the region’s countries that it supports their political independence and will take new steps towards creating “a China-centered economic circle” in Eurasia.

“This is basically a two-birds, one-stone strategy: to weaken Russian influence [and] to further integrate Central Asia more closely with China and its other [projects] in the region,” Ma said.

Source: https://www.rferl.org/