When Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoev’s eldest daughter and top aide, Saida Mirziyoeva, is paying visits to sick children in a hospital far from the capital, Tashkent, it is probably an indication that something serious has happened.

And when a minister is openly telling journalists not to look “too deeply” into something, it is a sure indication that someone, somewhere, has something to hide.

For over a week, Uzbek media and social media has been abuzz with the news of hundreds of children falling ill and dozens being hospitalized after taking medicine that was administered as part of a national campaign to battle iodine deficiency.

At the moment, the authorities are unwilling to admit the connection between the campaign and the children’s illnesses.

That hesitation is understandable.

After all, only last winter, 65 children died after taking cough medicine imported from India, triggering an outcry over a lack of oversight and alleged corruption in a fast-growing pharmaceutical market.

And although there have so far been no fatalities in this latest health-sector scandal, it is still highly sensitive for the government, which procured the prophylactic treatments that some 6.5 million children are eligible for, apparently at an inflated cost.

Since reports of children being hospitalized in the Ferghana Valley provinces of Namangan and Andijon began emerging last week, questions about official responsibility have been swirling.

At the moment, everything indicates that “some kind of conflict of interest took place,” according to Alisher Ilkhamov, director of the Central Asia Due Diligence research company based in the United Kingdom.

“Was a kickback paid to a public official? Or did the company have some kind of patronage connection with somebody influential, who promoted them at the highest level?” Ilkhamov asked in an interview with RFE/RL.

‘Hype On Social Networks’

Mirziyoeva said on September 23 that the Prosecutor-General’s Office had opened a criminal investigation into the hospitalization of more than 70 children in Namangan, during her visit to the province.

Photos published on her official Telegram showed her in a hospital ward with children lying in beds.

The post said that she had arrived in Namangan “on the orders of our head of state,” her father, Shavkat Mirziyoev, whose office had earlier expressed concern at the hospitalization of the children in that province.

“We went to the hospital to see the situation with our own eyes and received information about the condition of the children. They are in good spirits, everyone is slowly recovering, most have returned home to their families,” Mirziyoeva’s official Telegram channel noted, without providing details about the investigation.

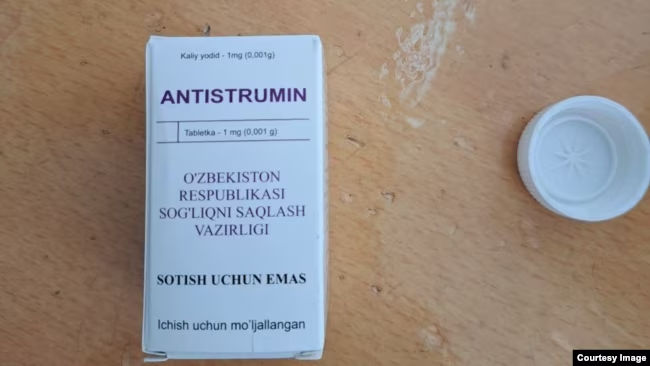

Deputy Health Minister Elmira Basitkhanova stressed on September 27 that the connection between the Antistrumin potassium-iodide tablets produced by the local pharmaceutical company Samo and the illnesses of the children was “so far unproven.”

Flu is a more likely explanation for the sudden surge in illnesses, suggested Basitkhanova, whose ministry suspended all use of Antistrumin on September 22.

Speaking to the news website Gazeta.uz this week, Orif Inamov, a doctor for the Republican Scientific Center for Emergency Medical Care, insisted that Antistrumin “cannot cause toxicity.”

“[If the dosage is large] then it is excreted in the urine,” said Inamov, who refused to discuss with the website’s journalists the reasons why children had to have their stomachs pumped and offered no update on blood analyses of the young patients.

Inamov instead blamed “hype on social networks” for the increased numbers of young patients visiting hospitals since the campaign against iodine deficiency began on September 20, while noting that most of the children did not require serious treatment.

Nodirbek Ischanov, an independent Uzbek medic and the country’s most popular doctor online, with a YouTube following of 3.6 million subscribers, has taken a different and influential view.

In a video published at the beginning of this week that has been viewed more than 1 million times, Ischanov said that dosages of the supplement indicated in a document published by the Health Ministry were “colossal” and capable of triggering side effects.

‘Provocative’ Reporting On Tender

Ischanov said that the tablet and half-tablet intakes recommended by the ministry for older and younger children equated to 1,000 and 500 milligrams of iodine, respectively.

That is several times the doses recommended by the World Health Organization, whose guidelines the authorities had earlier acknowledged on a website dedicated to the campaign, he pointed out.

So, is this a case of overdoses, rather than problems with the medication’s quality?

A simple miscalculation, or perhaps a typo, scaled up to affect children across the country?

Perhaps.

But the situation has logically increased scrutiny on the supplement’s manufacturer, Samo, and the manner in which the company achieved this massive contract.

Gazeta.uz’s investigating has generated new and uncomfortable questions on that front.

On September 26, the website cited data from the government procurement portal as showing that the Health Ministry’s procurement arm, O’zmedimpeks, had purchased Anstrumin in two batches of over 3.5 million boxes in total, securing the medication at the price of 5,500 soms per box last year ($0.45) and 6,600 soms per box ($0.54) this year.

Yet as Gazeta.uz was able to document, Anstrumin was available from several online pharmacies in Uzbekistan during this period at a retail price of around 3,000 soms per box.

This would imply the state not only failed to recieve a discount for buying in bulk, but actually paid more than twice Anstrumin’s retail value.

Those pharmacies are no longer advertising the product, but at least one confirmed the former price in an interview with the website.

In a press appearance on September 27, Uzbekistan’s health minister, Amrillo Inoyatov, denied that Anstrumin was available for a far cheaper price, stating that such claims had been published “untruthfully” and “provocatively.”

An aide to the minister added that the ministry had tried to secure a cheaper price but was knocked back by Samo, who the aide acknowledged was the only bidder for the contract.

‘Token Of Appreciation’

That Gazeta.uz was not invited to the press conference, and reported on it based on information passed by journalists that were at the event, says much about the darkening climate for journalism in Uzbekistan.

One major private media outlet that attended the presser, Daryo, published and then swiftly unpublished its report on what was said there.

In the latest version of Daryo’s article, Inoyatov’s exhortation for journalists not to report on the matter does not appear.

But Gazeta.uz, citing journalists at the event, reported that Inoyatov asked media not to “go too deeply into this topic.”

“There are organizations that are dealing with this matter,” Inoyatov said. “They are studying everything openly.”

The Health Ministry said on September 25 that it had begun its own investigation into Samo.

A few background checks before the deal with the company for the tablets was concluded might have raised red flags.

According to company documents shared by several Uzbek media outlets and bloggers this week, the business is essentially family owned, with all four founders sharing either a surname or a patronym.

Among this quartet is Nodir Yunusov, an Uzbek citizen who has been photographed at events promoting the company in Tashkent.

As the Kun.uz news website noted, Yunusov bears a strong physical resemblance to a man with the same name who has for more than a decade been wanted by the U.S. government to face charges of “human trafficking…rights violations, and financial extortion.”

In the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) official profile of Yunusov, he is referred to as one of three members of a “conspiracy” who “fled from the United States and remain fugitives” after law enforcement began targeting an outfit called Giant Labor Solutions more than a decade ago.

A Samo representative that Kun.uz contacted with questions about Yunusov’s identity stonewalled the outlet.

Official unease over the scandal is predictable, especially after the emotions stoked by last year’s alleged cough-syrup deaths.

The tragedy allegedly caused by the Doc-1 Max cough syrup, which was sold over the counter in pharmacies, is currently the subject of a trial in Tashkent.

A number of Uzbek officials stand accused of accepting a bribe of more than $33,000 from an Indian national — a representative of a company called Quramax Medical — to get around mandatory testing.

That Indian national, Raghvendra Pratar, who is also on trial, told the court that he had understood the fee as “a token of appreciation,” according to an August 16 Reuters report.

Source : RFERL